In 2011, Ethiopia announced the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in an act of historic significance. Leveraging the great Nile River, the African nation seeks to build the largest hydroelectric power plant on the continent. After over a decade of construction, the dam is almost complete.

The GERD promises to generate over 5,000 megawatts of power, doubling existing electricity production, improving food security through enhanced irrigation capacity and creating 12,000 jobs. This would increase national GDP growth by an additional 1.5 percent annually and stimulate foreign investment in the billions, which will speed up its industrial transition across economic sectors. Upon completion, the country will be revolutionized, as access to power will dramatically increase across the nation from the interior to the capital city, Addis Ababa.

This is a particularly welcomed development for Ethiopia, which has experienced a nearly uninterrupted series of ethnic wars since the fall of the Ethiopian Empire in 1974. Wars against the Somalis, Eritreans and the Tigray have threatened to tear the country apart, and today’s violence between the majority Oromo and Amhara communities scream out the need for national unity. For many Ethiopians, all they’ve known is war, so the GERD is far more than just a dam.

For Nimeni Tadesse, a masters of architecture Ethiopian student at Howard, it is a powerful sign the country is moving in the right direction.

“Everyone was just encouraged. I remember it was that one thing everybody agreed on. It didn’t matter what region you were from, [or] what ethnicity you were, there was literally no other option. To this day, it is the one thing that will unify us. It was like a beacon of hope,” she said, describing her experience soon after the GERD’s announcement.

It’s no exaggeration because this isn’t just about Ethiopia. The GERD’s set goal, once it generates sufficient energy domestically, is to export energy to its underdeveloped neighbors.

In a report by the Arab Center Washington DC from 2022, Ethiopia was noted as “one of the least economically developed countries in Africa, with more than half of its roughly 117 million people lacking access to electric power. But the country plans to reach 100 percent electrification by 2025, in large part due to hydroelectric power produced by the GERD.”

This would offer significant legitimacy to the project, strengthening intercontinental economic relationships, and therefore promoting security from the Nile Basin to the Great Lakes region.

Egypt, however, is concerned.

Since the times of the pharaohs, the Nile has defined the country in every way that matters. This has had an enormous impact on its foreign policy upstream, and this has not effectively changed.

The harsh geography of the Sahara Desert demands that the overwhelming majority of Egyptians live along the river. As opposed to the Sahara and Sinai deserts, which are inhospitable, the Nile provides Egypt with 90 percent of its water, sustaining its energy production, agriculture and drinking water for its fast-growing population. This is no revelation, and therefore for millennia, it has been the job of any Egyptian leader to ensure that the flow of water upstream is unabated.

This is why in 1929, shortly after formal Egyptian independence, the British signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, granting Egypt authority to unilaterally reject any infrastructure projects along the Southern Nile River Delta.

Of course, Ethiopia strongly denies the validity of Egypt’s deal with Britain, especially since it was excluded from the negotiations at the time. With the global proliferation of technology over the last century, the stakes of not building the GERD have risen dramatically. Without a means of increasing energy production fast, Ethiopia risks being left out of the 21st century, forcing Addis Ababa into a state of desperation.

Unfortunately for Ethiopia, however, Egypt’s control of the vital Suez Canal trade route offers it support from powerful partners, like Britain in the 20th century and the U.S. today. This support has contributed negatively to stability in the region, however, Egypt’s national security is seen as a higher priority.

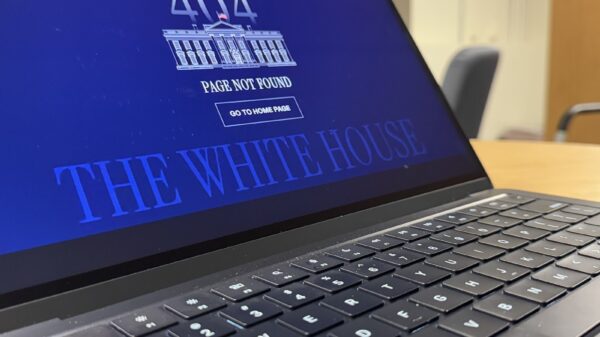

In 2020, the Trump Administration mediated in peace talks between Ethiopia and Egypt, proposing a deal that would grant Egypt regulatory power over the GERD’s operations.

Ethiopian dignitaries said the U.S. was “undiplomatic” and “diverging from its role as mediator” in the negotiations, so they promptly continued its construction, but the failed discussions in 2020 drove a wedge between the two parties and marked a turning point in Ethiopia’s foreign policy alignment.

Seeking international allies, Ethiopia joined the BRICS system in 2024, an international organization of countries dedicated to upending U.S. unipolar global power. This has pushed Ethiopia into the same camp as Russia and China, two countries that share a dominant influence as founding members of the group, yet Ethiopia still feels like they’re left without options.

Meanwhile, Egypt has begun positioning itself for conflict, securing defense cooperation agreements with Sudan, Somalia, Kenya and South Sudan. Ethiopia now finds itself in a position where its borders are entirely surrounded by countries hosting Egyptian troops—troops that can be deployed to attack from all directions in the event of war. Under any other circumstance, a country in this position would cave to all demands, but there is a resolve in this matter that cannot be easily swayed.

Alem Hailu, PhD, an Ethiopian professor of African studies at Howard believes Ethiopia’s position in this crisis is emblematic of the modern African reality.

“Egypt is selfish. They have no right to claim the river as only their own. We just want a fair share, but they don’t want to hear it,” he said.

Ethiopia, by contrast, faces the challenge of asserting its sovereignty and developmental goals while navigating a global order that often prioritizes the strategic interests of non-African powers. For Egypt, substantial military aid shipments from the U.S., their geopolitical ally, provide the leverage to build security alliances with upstream countries that might otherwise oppose its objectives, allowing it to encircle Ethiopia and intensify the threat of war.

A recent graduate of the Institute of World Politics’ Statecraft and International Affairs master’s degree program, Ashton Earl, pulled on his research focused on the Middle East and North Africa to empathize with the Ethiopian position, but argues that the strategic implications of building the GERD are costly.

“The energy is the biggest deal for them [Ethiopia], and that’s what they’ll say to anybody; I think there’s a lot of truth to that. But on the other side, it will provide Ethiopia with a lot of strategic leverage over their neighbors to be able to control the Nile against anyone else who has eyes on the Nile,” Earl said.

Today, Egypt suffers from high inflation, political instability, urban overpopulation and its precarious position amidst failed states like Libya and Sudan, as well as territories like Gaza. Each exposes weaknesses that can be easily exploited. Despite this, Egypt continues to hold significant support from the Arab League and its Western allies. This strategy, when deployed against its fellow African states, often highlights a recurring theme of detachment from the continent—Egypt’s detachment from Africa. Such a posture risks alienating its neighbors and perpetuating an inevitable cycle of conflict, where Ethiopia acts only as a precursor of what is to come.

Egypt’s concerns regarding the Nile cannot be dismissed—they are grounded in historical, cultural and existential realities. However, these concerns must not translate into selfishness. While Egypt is the Nile, the Nile is not Egypt. A sustainable solution requires Egypt to recognize Ethiopia as a peer nation rather than a subordinate one. Only through mutual respect and equitable dialogue can both nations find common ground.

The international community, particularly the United States, must adopt a more balanced approach when mediating this crisis. A policy that disproportionately favors Egypt, risks driving Ethiopia further into isolation, increasing the likelihood of a military confrontation.

Should this conflict escalate, the global economic repercussions would be catastrophic, with a ripple effect across a region already plagued by continuous war and instability.

If true peace is to be achieved, the world must prioritize dialogue over domination, equity over exclusion and collaboration over conflict. The stakes are far too high for failure.

Copy edited by Anijah Franklin