In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to remove “the biggest bottleneck to Africa’s development,” which is infrastructure. While a global initiative, Africa has been targeted, with over $700 billion invested in modern highways, railroads and more by Chinese state-owned construction companies, according to Voice of America. This development has sparked a blend of shock, joy and fear globally.

The mixed reaction is the result of a successful messaging campaign by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that its goals to overthrow the West and economically develop each other after colonialism are shared. The African Union Representative to China, Rahamtalla M. Osman, reinforced this claim. In a 2023 report by the Chinese state-owned news blog, PR Newswire quoted Osman, saying the BRI is “a win-win cooperation, not a charity.”

Across Africa, there are projects that have on paper allowed the opportunity for countries to ease their industrial transition. China has invested in dams in Sudan, bridges in Mozambique, expressways in Algeria and railroads throughout Africa in Ethiopia, Kenya and as far as Nigeria, so the BRI is seen as giving Africa the chance to catch up to the world. All this, though, has come with a cost.

Economists have long warned that Chinese loans don’t produce independence or development where they need both. Rather, there’s growing evidence since the BRI’s launch that the project saddles countries with debt, with little positive impact on the recipient country.

Brahma Chellaney of Project Syndicate wrote in January 2017 that the initiative was designed to “use economic tools to advance their country’s [China’s] interests,” directly contradicting the CCP narrative.

The BRI program runs under the condition that China loans money to finance the construction of key infrastructure. After a period of time agreed upon between the local government and the Chinese-based company, the country will repay the loan with the anticipated profits. Innocent enough, but the African continent is littered with countries facing economic collapse as a result of the BRI.

In Kenya, BRI projects led to public debt rising to $80 billion, with the debt-to-GDP ratio far more than the IMF recommendation, according to Statista. Facing economic collapse, William Ruto was elected as president in 2022 to reduce dependency on China.

Seen as the only way to reduce the national debt, Ruto sought to prevent further pressure from China and the IMF by heavily raising taxes on citizens with his finance Bill, despite extreme internal pressure. Over the summer, however, Ruto was forced to reject the bill after weeks of protests and 400 young Kenyans dead and injured, as reported by CNN.

In response, the Kenyan government was forced to cut the equivalent of $3 billion in government services to account for the loss of revenue. Meanwhile, China is waiting on billions of dollars due by 2025, which, if unpaid in full and on time, many believe could lead to the seizure of the Port of Mombasa. This forces Kenya into an unfavorable position where it would seem that one step forward brings them two steps back.

This is the problem with Chinese-funded development projects like the BRI. Hudson Institute’s senior fellow expert on Africa Joshua Meservey argued that the BRI is built on a shaky foundation of cognitive dissonance.

“These problems hurt its image on the continent when so frequently, they talk about win-win cooperation and brotherhood going back to the liberation struggles and also when they demand to get paid,” he said.

China toes a fine line between partnership and strategic interests, which don’t always align. For decades, they have developed friendships, but these are not out of kindness alone. According to Meservey, “China wants to get paid, fundamentally,” and this shapes their entire Africa policy.

China’s not bringing anything new or valuable to the continent. China builds railways and highways from the interior to the ports so they can ship minerals out rather than promote self-sufficient regional trade. China mines countries for resources, but does not authorize nearly enough processing and refinement plants there to provide any value-add en masse.

China builds airports but refuses to facilitate social programs that will stimulate wealth among local people to afford air travel. China authorizes the construction of schools, but only so they can shape the next generation of African leaders. China refused to hire locals, despite a continent-wide unemployment crisis, and when they finally did hire them, they committed gross human rights violations.

And remarkably, despite the bilateral trade volume between China and Africa increasing by a factor of 28 since 2000, according to the Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). GDP per capita has also simultaneously increased from $1,458 in 2000 to $2,273 in 2023, according to Statista. Despite the propaganda, they are as bad or worse than today’s West. China does not want independence, they want vassals.

This mix of factors leads to Africa becoming a very politically combustible region in the coming years. An expert on China-Africa relations, Howard’s Phiwokuhle Mnyandu, believes America is in a prime position to counter.

The BRI is an economic and political project, but the cultural aspect is neglected. With skepticism toward China increasing, the U.S. can undermine China while African countries are recognized as key partners, providing an ideal marriage of interest. Given past grievances, rolling back Chinese influence will involve a significant engagement with the African diaspora.

“America gets to now govern in essence a new African Renaissance culturally, and that’s a big deal,” Mnyandu said.

It can already be seen today, as the U.S. government invests heavily in engaging young Black Americans for a new Afro-centric foreign policy through HBCUs like Howard.

Howard’s invitation to programs like the Department of State’s Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) Fellowships and the Academic Centers of Conflict Anticipation and Prevention, Department of Defense’s University Affiliated Research Center, the director of national intelligence’s Intelligence Community Centers for Academic Excellence for aspiring Intelligence Community (IC) professionals are no accident. They are rather built to usher in the next generation of Black thought leaders because until recently, U.S. foreign policy in Africa has been lost.

The U.S. began its relationship with today’s Africa by promoting, and often forcing independence shortly after World War II, but it attempted to ride the line of its European partnerships, becoming complicit in some of the modern world’s greatest violations of international law.

On the other side, the Peace Corps and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) have been criminally overlooked. At this year’s China Forum, former U.S. Ambassador to the UN’s Economic and Social Council Kelley E. Currie strongly defended U.S. policy of foreign aid, arguing that “[T]he idea that the United States is not committing sufficient resources to what we’re doing globally is frankly nonsense. We contribute $18 billion annually to the UN system across all channels. China puts in a fraction of that,” and that should not stop.

Mnyandu said that he is against people saying that America ‘needs to do more,’ because he believes America is already doing a bunch.

He said, “It’s just that the Peace Corps are told to keep their heads down, don’t be showy, but the Chinese walk there and make sure they let the people know they are there by the grace of the Chinese people.”

This fuels the notion that the U.S. isn’t even there, but it is. For this reason, Currie believes that the dynamic between U.S. diplomats and African leaders has been tainted as a result of good acts not being advertised.

“The U.S. shows up to these countries, and leaders question what we have done for them lately. We say, ‘Well, you know, we just saved a quarter of your population from dying from AIDS. Was that okay? Did we do the right thing there?’” Currie said.

She believes that the U.S. operates almost silently in the background, and they must do a better job of making people realize that they contribute to these global public goods in meaningful ways that Beijing does not.

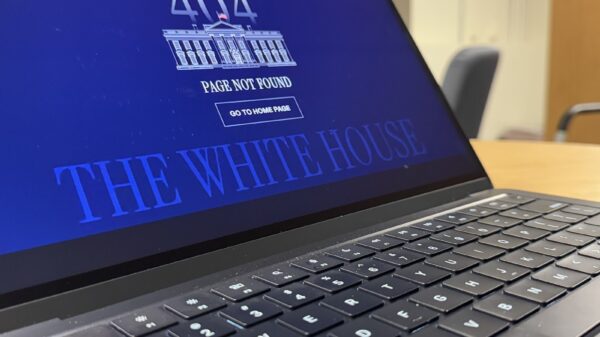

It’s also about respect. U.S. presidents historically don’t visit Africa, and Biden hasn’t gone once. Even rarely when a president does meet with African leaders, within the White House, it’s in groups. In China, however, leaders speak as peers.

“The last presidential summit, African leaders complained, because only four or five of them met with the U.S. president bilaterally. The rest of them gathered for photos,” Mnyandu said.

With China, however, especially with the recent FOCAC Summit in September, Mnyandu explained how “Every single one, even a country with only a five-person population, was treated like a VIP. African countries have an inferiority complex about these things, they remember how painful it is to be undermined.”

Any U.S. counter, therefore, must account for this, because they have an enormous impact on politics. So as the BRI is increasingly pressured, and this new scramble for Africa emerges, the U.S. can create more equitable moral standards with its African relations that leverage existing strengths and untapped resources.

Through respect, partnership and cultural diplomacy, Howard can lead America’s campaign for peace, freedom, prosperity and development, providing an authentic alternative to China.

For this, the African diaspora is needed. In this truly postcolonial African reality, Black Americans can no longer protest policy from the outside, but work to fix it from within to bring about a better future for black people. So, fellow Bison, let them see us.

Copy edited by Camiryn Stepteau