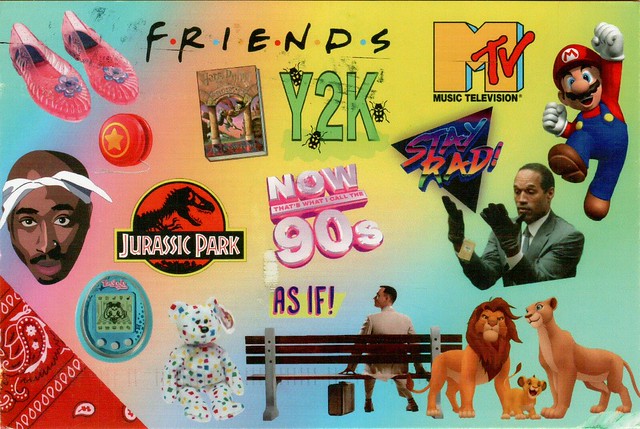

From low-rise jeans and Juicy Couture tracksuits to baggy cargo bottoms and music that echoes decades-old hits, our cultural landscape is deeply influenced by a desire to revisit the past.

It’s 2024, and Gen Z is captivated by nostalgia and eager to recapture the essence of the ‘90s and early 2000s. This generation is at the forefront of the revival of Y2K aesthetics, reboots, and constant sampling in music.

Hollywood reflects this collective yearning as they churn out multiple sequels and reboots of films from our childhood. Although trends are undeniably cyclical, this generation’s intense focus on the past raises the question: Where do we draw the line between inspiration and imitation?

In early August, Disney’s D23 expo announced a few nostalgia-driven projects, with five out of seven new titles being sequels or reboots of old favorites like “Frozen 3” and “Toy Story 5.”

This extends to live-action remakes like “The Lion King” and “Beauty and the Beast,” which have proven financially successful, collecting over $1 billion at the box office.

According to the L.A. Times, “Sequels, threequels and spinoffs seem to be the name of Disney’s current game.”

But Disney is not alone. Franchises like “Fast & Furious” and upcoming reboots like “Karate Kid” and a fourth “Jurassic Park” reflect Hollywood’s reliance on tapping into past sentiments rather than innovating by taking the same stories that appealed to our parents and marketing them to us.

Beyond possible corporate-generated nostalgia, this craze extends beyond movies and permeates throughout my generation in full force.

Gen Z loves to reminisce. Scroll on TikTok, and you’ll find young people longing for relatively recent periods that may not seem distant enough in time to claim nostalgia, like the 2020 pandemic or the summer of 2016.

Keep scrolling, and you’ll run into slideshows set to somber sounds, filled with images of our childhood. For example, classroom holiday parties with images of “The Polar Express” and hot cocoa.

But what I find interesting is Gen Z’s yearning for something we never experienced. On social media, around campus, and especially at Howard, you can see that Y2K fashion, music, and overall vibe have resurfaced, yet most students weren’t born or were toddlers during this era.

Jayna Renna, a junior, photographer and model for Howard University Elite Models, said she’s seen the resurgence.

“Both personally and through Elite, I see it a lot,” she said. “The resurgence of fashion is trendy, but it’s also been around for a long time. I just think people find a lot of comfort in nostalgia, and to bring it back, it makes new ideas and old ideas kind of mesh together, which is nice.”

In part, I think our fascination with the past is tied to the fact that, as people, we tend to desire the things that we don’t have, including what we don’t have anymore—whether it be our youth, our childhood, or the experience of growing up in the early 2000s.

In Retromania, Simon Reynolds explores our cultural fixation on the recent past.

“Never [has there] been a society in human history so obsessed with the cultural artifacts of its own immediate past,” Reynolds wrote.

But this obsession with the past isn’t exclusive to Gen Z. In the 1970s, there was a fascination with the 1950s, reflected in the film “Greece” (1978). In the 1990s, similar fantasization and romanticism surrounded the 1960s.

This pattern is known as the 20-year cycle, in which every 20 years, trends and fashions repeat and resurface. What was once outdated has the opportunity to gain a second life, especially if it evokes feelings of nostalgia and familiarity.

However, the length of these cycles appears to be shortening as the rate at which trends resurface speeds up. People have already begun expressing nostalgia for the 2010s with playlists and accounts dedicated to the era. But why are people yearning for times that are barely a decade old?

I fear our obsession with nostalgia has created cultural stagnancy, where we recycle old ideas instead of innovating. Although the past can be a source of inspiration, we must seek balance so that we don’t risk missing out on defining our present with its own unique trends and cultural touchstones.

Copy edited by Anijah Franklin