Following a unanimous vote of 87, Togolese lawmakers approved constitutional changes to transition the country from a presidential to a parliamentary system, allowing the parliamentarians to elect the president of the republic, according to Africa News.

“The head of state is practically divested of his powers in favor of the president of the Council of Ministers, who becomes the person who represents the Togolese Republic abroad and effectively leads the country in its day-to-day management,” Tchitchao Tchalim, chairman of the National Assembly’s Committee on Constitutional Laws, Legislation and General Administration, said, based on reports from Le Monde.

The new legislation drastically differs from the 2019 amendment to the Togolese constitution, which established a two-round presidential election process and stated that the president of the republic is chosen by universal suffrage for a five-year term that is renewable once.

Opposition parties and civil society groups have once again called for protests after the Togolese government recently banned protests over the new legislation. The Gnassingbé family’s 57-year rule was obtained in Sub-Saharan Africa’s first military coup d’etat, according to the African Journal of Legal Studies.

Based on reports by France24 News, supporters of the new constitution say that the modifications lessen presidential powers by essentially turning the presidency into a ceremonial position, imposing a one-term limit, and giving more power to a figure resembling a prime minister.

Given the change to a parliamentary system in which his party is the majority, Gnassingbé will likely be reelected in 2025, when his term ends, enabling him to stay in power until 2033. Opposition leaders fear the new constitution will extend the near two-decade rule of President Faure Gnassingbé, who came to power in 2005 following the death of his father.

“Togo has just turned a new page on its way towards a more inclusive and participatory democracy. This is a satisfaction and a source of pride for us,” Minister MP Germaine Kouméalo Anate, a politician from Gnassingbé’s ruling UNIR party, told reporters after the vote, according to Barron’s. “More stability for our country and more transparency in governance. It is a source of pride and we consider that it is a reflection of the will of the people.”

Opposition parties argue that Gnassingbé may use the position—officially known as the president of the council of ministers—to consolidate his hold on power, as the family’s grasp on power was on display following the deaths of over 20 people during months of anti-government protests in 2017, as reported by The New York Times.

Jude Kouassi, a senior biology major and chemistry minor from Omaha, Nebraska, by way of Lome, Togo, thinks the new legislation is a step in the wrong direction.

“The ratification doesn’t seem to make sense for a democracy, and I don’t know how to feel. It feels like things have been the same in different ways for the past couple of elections, with no real input from the people,” Kouassi said. “I hope the younger generation is able to mobilize ourselves and make some changes.”

The new constitution lengthens presidential terms from five to six years, meaning the new term would not include the nearly 20 years that Gnassingbé has held office following his father’s death.

Nnayelu Oranuba, a senior finance major and philosophy minor from Rockville, MD, by way of Nigeria, thinks that the process of amending constitutions and moving away from colonial influence is a positive thing.

Oranuba shared that he is conflicted about the new change in Togo as his own country, Nigeria, has also experienced significant regime changes that have resulted in a transition of power or, in most cases, a stronger hold on it.

“I know in Nigeria there has been a lot of corruption with political leaders and legislation being written to keep them in power,” Oranuba said. “So it’s really up to us to bring attention to and make amends to these changes.”

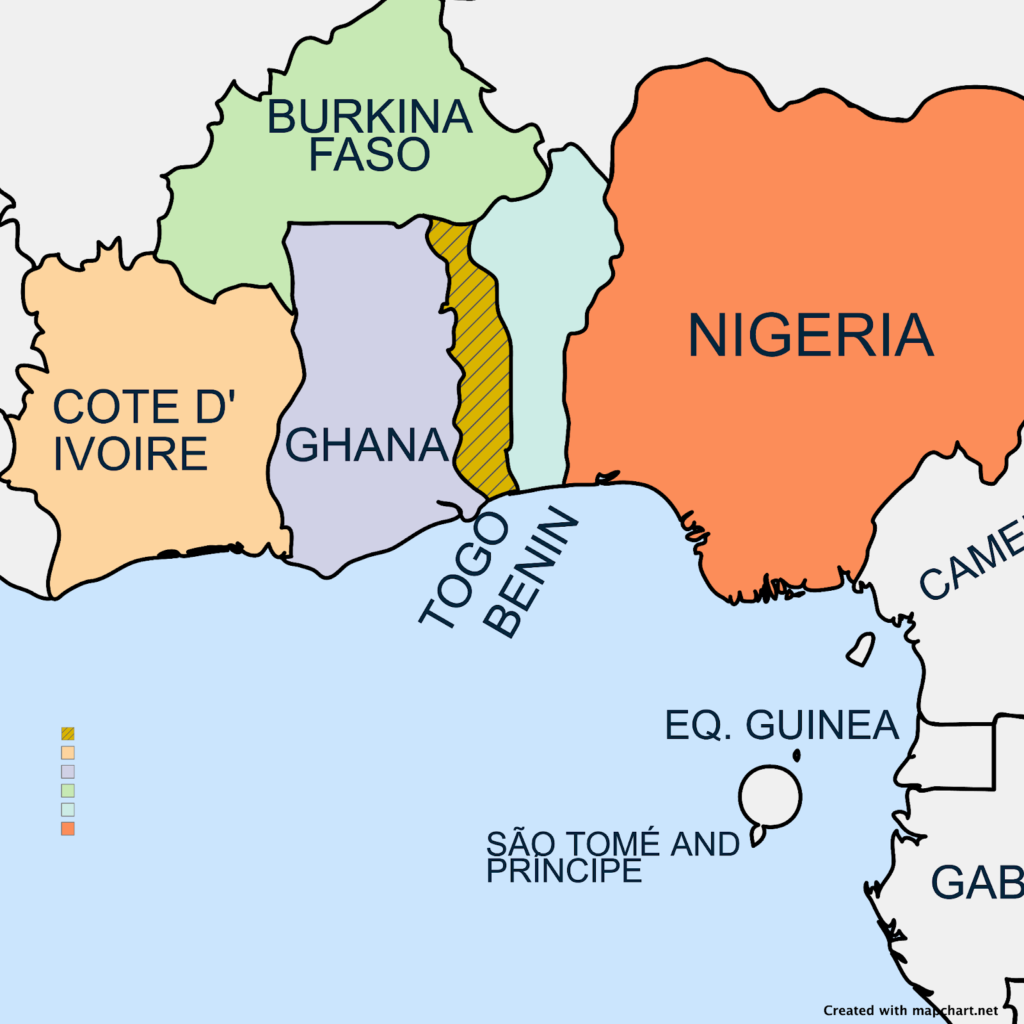

According to BBC News, the new legislation is not an isolated event; instead, the unauthorized constitutional amendments, election postponements or succession crises, such as those in Togo, are part of a series of changes heightening tensions across different West African countries like that of the current crisis in Senegal, continuing to be a compelling illustration.

In recent years, several African nations, such as the Central African Republic, Rwanda, Congo Republic and Guinea, have restructured their constitutional and other legal modifications to permit their presidents to serve longer terms. There have also been eight military coups in the West and Central African region within the last three years, which further pressured the coastal country to make a change in its government.

Komlan Avoulete, a Sahel researcher, geopolitical analyst and freelance writer, said Article 2.1 of the ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance states that “No substantial modification shall be made to the electoral laws in the last six months before the elections, except with the consent of a majority of political actors.”

For members of the international community, including some Togolese diasporans and West Africans, ECOWAS’s silence on the country’s constitutional amendment is shocking but not surprising.

Oranuba discussed the realities of being a young West African student at Howard University and seeing these changes occur on the continent while being in the U.S.

“I go back to Nigeria often and I know that changes in West Africa influence other countries. It’s interesting being on the outside and looking in, and also examining how these situations allow me to navigate life better when I return,” Oranuba said.

Copy edited by Jalyn Lovelady