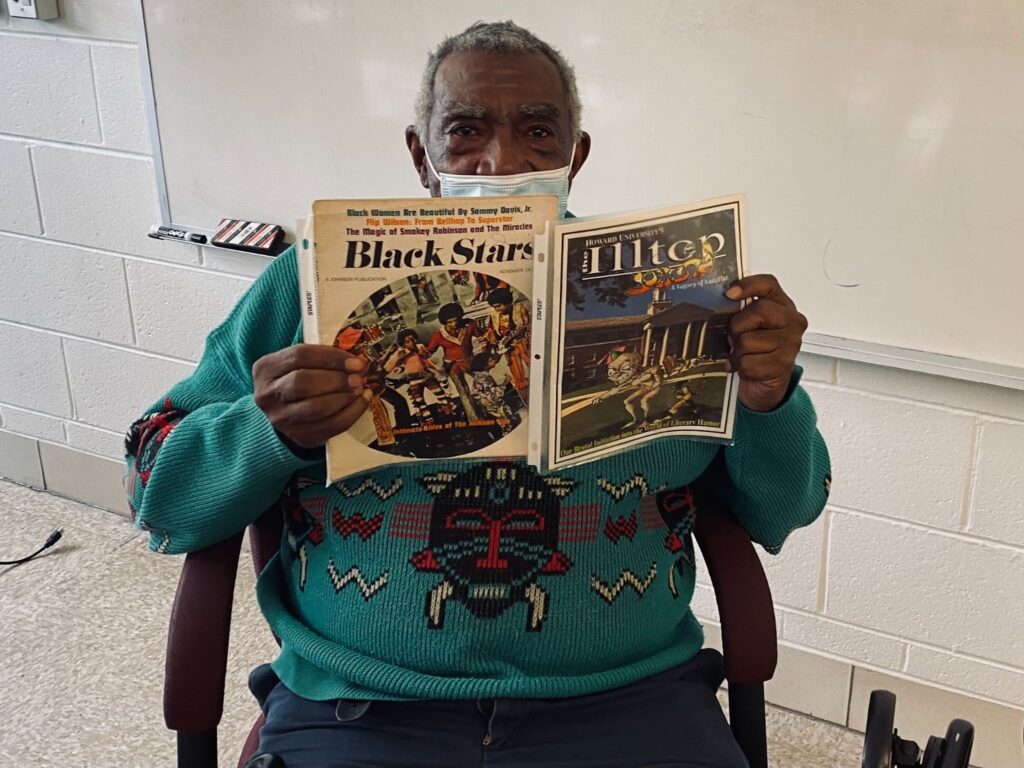

The Hilltop sat down to chat with one of Howard University’s most treasured alumni, Alfonzo Peter Bailey. Bailey, 84, is a journalist, author, lecturer, historian and former associate of Malcolm X. The conversation outlines his personal story and reveals how he developed an important relationship with history.

In the beginning of the interview, Bailey discussed his childhood. He was born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1938 but would spend the school year with his grandparents in Tuskegee, Alabama, because his father, who was in the military, traveled throughout the year.

Bailey: In elementary school I attended St. Joseph’s Catholic School, which was a Catholic school run by Irish Catholic priests and Irish Catholic nuns – there were no Black nuns or priests at that time; I never even knew that there was any such thing.

Jean-Jacques: And this was in Tuskegee?

Bailey: This was in Tuskegee – and what happened is that they came to Tuskegee and built the schools, ‘cause you know the schools were segregated at that time… and there were really practically no Catholics in Tuskegee at that time.

Bailey excelled in first grade to such a degree that his teacher put him in the second grade early. He completed half of first grade, half of second grade, then he went to third grade. He graduated from St. Joseph’s, then went to a public high school.

Bailey – I didn’t know it then, but that was the beginning of my knowledge about history because those nuns – they were Irish-Catholic nuns, every single one of them. When they taught us history, man, they taught us history from an Irish-Catholic perspective… They talked about British history very badly; they taught us history from a Irish-Catholic perspective. I remember, brother, that we would have assemblies, and we had, Easter Sunday, Christmas and St. Patrick’s Day – no Black holiday, but we celebrated St. Patrick’s day, man – we knew more about Irish history, I’m telling you; from the first grade to the eighth grade, I learned ten times more about Irish history than I…did Black history. I learned nothing about Black history, not a single thing.

Jean-Jacques: Were you aware at that time? Were you–

Bailey: No, absol– I had no total awareness. Now, when I left there, I went to the public high school, which was Tuskegee Institute High School. They called it that because the high school was up near the campus [of Tuskegee University].

Jean-Jacques: And how old were you then?

Bailey: I was– well I graduated from eighth grade when I was 13…

Bailey later left Tuskegee and traveled to Nuremberg, Germany, with his family because his father was stationed there. He discusses how he went from schooling in a predominantly Black high school in Tuskegee to being the only Black student in his classes in Germany. He returned to the United States after three years in Germany, and began thinking about college.

Bailey: My parents and everybody wanted me to go to Tuskegee, but I didn’t want to go there. I don’t know why, but I wanted to go to Howard. So, I said, ‘here’s what I’m gonna do – I’m gonna join the military, do my three years in the military, and then get the G.I. Bill – what they called the G.I. Bill of Rights – and use that money to go to Howard.’ So that’s what I did. And the funny thing is that six months after I got through basic training and all the stuff your training goes through, I was stationed right back in Germany. So between the ages 15 and 20, I spent most of that time living in Germany, but at this time I’m still, you know, kind of – politically unaware, I wanna call it.

Jean-Jacques: How do you mean?

Bailey: I do remember seeing things, brother, that was like, I call it my ‘wake up call.’ It’s when I was 17 years old and the Emmett Till case happened – and I saw that Jet Magazine – that picture of his body. That’s when I really– I started becoming, I guess you would say, more politicized then.

Jean-Jacques: Because of Emmitt Till…

Bailey: Yes

Jean-Jacques: And what do you mean by more politicized? Was it just an anger? Was it–

Bailey: Anger– I mean I literally had tears in my eyes, man. Cause he wa– like I’m 17, he’s 14. And I really– that really hit me, and you know, I always say that that was kinda like my wake up call – in terms of race.

Bailey recounts how he had gotten very familiar with discrimination having grown up in Tuskegee. He mentions, however, that as a child he had never really acknowledged the concept of race. According to him, during his childhood, Macon County, Alabama, was about 85 to 90 percent Black – the only white people he would see were the nuns and truckers.

Bailey: I remember sometimes sitting in those classes, and hearing those white teachers talking about, you know, slavery and those kinda things, and they didn’t praise slavery, but they also didn’t condemn it. And of course, I knew nothing, but I just felt as though ‘something is wrong,’ you know; but I never said anything ‘cause I didn’t know enough. I didn’t know nothin’ about Frederick Douglass and Martin Delany and Nat Turner, I didn’t even know those names, brother.

Jean-Jacques: So they didn’t really teach you the important parts of Black history, and when you heard about Emmett Till, and when you saw that picture in the Jet Magazine, how did that, you know, change your perspective or what did you maybe start teaching yourself?

Bailey: It made me very, very race conscious. And that’s when I began to read more and learn more about the real deal of this country in terms of race; ‘cause growing up in Tuskegee, which was like about 90 percent Black, and going to, you know, schools that were all Black and going to those– I really had not run into the real deal about racism in this country until I saw that picture of Emmett Till.

Bailey reiterates the fact that most of the people he saw in Macon County were Black and that he was not yet race conscious. The Emmett Till case made him more racially aware, and at 17, he decided that he wanted to attend Howard University.

Jean-Jacques: Well when you went to Howard, could you talk about your experience and what were some key moments here that stuck with you?

Bailey: It was at Howard University that I had my first introduction to Black history, and the professor’s name was Dr. Harold Lewis, and I remember– the first day of class, I signed up to take the course– I had heard nothing about him, knew nothing about him, but I just knew I had always liked history, so I saw the course, and then Dr. Harold Lewis said to us on the first day of class – I’ll never forget it – he said, ‘all your lives you studied history of people of European descent. In this class you’re gonna be studying the history of the rest of the people in the world.’ And that’s where I was introduced to African-American history, African history, some Chinese history, some Japanese history and some Native American history. I mean that class was un– I’ll never forget that class. That’s where I began to hear about Martin Delany and Frederick Douglass and Nat Turner and Hariet Tubman, and this is– I’m 20 years old, brother, before I even heard these names.

Bailey started at Howard in 1959 at the beginning of the spring semester. He stayed in Newmans dorm, which is now known as Drew Hall. From his first history class with Lewis, Bailey became a history enthusiast.

Jean-Jacques: Well on that topic, obviously right now we’re in Black History Month, and Black History Month for the past couple years, there’s been a lot of events, a lot of national recognition. In the same vein, what does Black History Month mean to you personally?

Bailey: The person who helped me to get at what it means was the great Lerone Bennett Jr., who was an editor with Ebony Magazine, and in 1982– and of course by that time I had begun to become aware of history and started to go to things, but it was Lerone who put history into the kind of things that made a whole lot of sense to me. I remember in an article that he wrote in August, I think it was August 1982, no, February 1982 issue of Ebony Magazine. He wrote an article called, “Why Black History is Important to You.” I would recommend that everybody read that article, he has– one part of it he says ‘the past is a bet that your fathers placed that you must now cover,’ and to me that’s one of the greatest lines I have ever heard in my life – ‘the past is a bet that your fathers placed that you must now cover.’ ‘Course, when I use it at this time I always say– I change the one word. I always say now, ‘the past is a bet that your ancestors placed that you must now cover,’ ‘cause you know the sisters’ll get very upset if you just say fathers, so I changed that one word. I don’t think Jerome will get upset with me for changing that one word. The past is a bet that your ancestors placed that you must now cover. And I think that’s the best reason I have ever seen anybody make about why studying history is important.

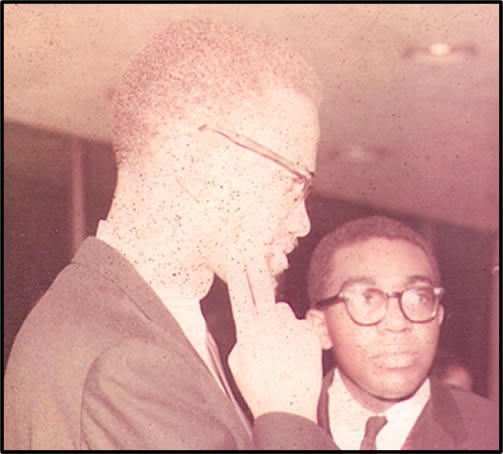

Bailey had become very serious about studying Black history, but his passion was reinforced when he listened to a Malcolm X speech in the summer of 1962 at Mosque No. 7 in New York.

Bailey: One of the things that first attracted me to Brother Malcolm was the very first speech I ever heard him give. He talked about history. I never heard a public speaker speaking outside to a crowd talk about history the way he did that afternoon. And then he talked about psychological warfare – I had never heard anybody talk about psychological warfare.

Jean-Jacques: Yeah – I remember watching a documentary and he mentioned psychological warfare, and I’m like ‘that’s, like a completely nuanced concept that people don’t really consider.’

Bailey: Well after hearing that first speech, I became an immediate ‘Malcolmite’ ‘cause I never heard anyone talk about the race and white supremacy in this country with such clarity and passion and knowledge. From that time on, whenever he spoke anywhere in the New York City area, I was there, and if he mentioned a book or a news article I would find those things and read them and this is the way I was introduced to him.

In January of 1964, a friend of Bailey’s, Lin Shifflett, asked him if he would like to become a part of a new Black nationalist group called the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Bailey would later find out that the organization was founded by Malcolm X. She called him the following week, and soon after, the pair met at a Harlem motel.

Bailey: When I got over there, there was the conference room on the ground level, so I just walked right into the conference room and I saw Lin and her roommate who I knew. Dr. John Henrik Clarke, he was there, John Oliver Killens, the author, was there and about four or five people who I did not know at the time. So we sat around talking about all kinds of different things, then after about 15 to 20 minutes, in walks Brother Malcolm, and when he walked in I almost fell out of my seat ‘cause I had no idea that I was getting ready to be a part of an organization with Brother Malcolm.

The organization was announced publicly on June 28, 1964. It consisted of various committees focused on economics, politics and communications. Bailey volunteered to be in the communications committee, and this was what he described to be the introduction to his career in journalism. He was 25 at the time, and his involvement with the organization was how he became actively involved with Malcolm X.

Bailey: Brother Malcolm was a great human being, a great Black man, a great pan-Africanist and a master teacher, and in the very first issue of the newsletter, I dealt with him as a master teacher. In the very first article that I wrote in my life, I covered – in 1964 this white cop had shot and killed this 15 year old Black boy and it started the Harlem Uprising in 1964. Brother Malcolm was travelling in Africa at time… and [over the phone] I read him what I had written about that incident, and I remember saying ‘eyewitnesses to the murder,’ and he stopped me and said ‘no Brother Peter, you can’t say ‘murder’ because ‘murder’ and ‘murderer’ are legal terms that you can only call someone once they’ve been convicted, and we know this cop will be acquitted… So he said, ‘call him a killer and refer to it as a killing because it’s a killing no matter what the circumstances.’ That’s when I saw directly the master teacher, and that’s something I’ll never forget.

The organization published 9 issues before Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. Bailey goes further into Bennett’s “Why Black History is Important to You” and talks about the debt that he believes Black people today need to cover for their ancestors.

Bailey: You start thinking, man, you owe that to your grandparents and your great-grandparents and your great-great-grandparents, you know. I thought that [Bennett wrote] an incredible quote, man, and I use it quite a bit when I’m speaking about history, and I– I mean not quite a bit, I use it all the time, everytime I’m speaking about history.

Jean-Jacques: Well what do you think is the biggest misconception that people may have about Black History Month and its meaning?

Bailey: My only thing is that we have to understand as a people – I don’t care what the larger society does – Black History Month should be a month of celebration, but we should be teaching our children Black history every single day, and I think it’s really really really, very very almost child neglect, for those Black people who just teach Black history during February. I mean– I think that’s wrong, man. That is wrong – you should be teaching your child Black history every single day of the year.

Bailey speaks about how, during his childhood, he noticed that many Black people did not know much about Black history, that they didn’t know figures like Martin Delany or Harriet Tubman. He emphasizes that although the point of February may be to celebrate Black history, studying Black history is something that we should make a habit of in our lives. Bailey also asserts that studying accurate Black history is critically important – he recalls a time when he voiced this to his son’s teacher.

Bailey: I went to one of my boy’s classes, one of his teachers was telling me – and this teacher, a white teacher, talkin ‘bout, ‘the benefits of slavery.’ That ‘it got the African people out of the wilderness of Africa – blah, blah, blah, blah, blah – though it was evil, in the long run it helped the people of Africa.’ Man, when my son told me that, man [laughter]. I went over to that school and I talked to that teacher.

Jean-Jacques: Oh, did you?

Bailey: Oh, yeah.

Jean-Jacques: What did you say? What did you tell the teacher?

Bailey: I just basically said that, ‘what you taught my son is basically a lie.’ I said that ‘you should stop teaching or telling Black children there was some kind of good side to the enslavement of African people – no such thing. ‘There was some positive side of it because Africans were brought into the civilization.’ Man, I mean. That teacher eventually left.

The conversation shifted to the subject of Florida’s banning of ‘critical race theory’ from classrooms as well as the exclusion of other historical subjects. Bailey speaks to why it is important for students to be taught the full history of America, and why historical inaccuracies need to be pointed out.

Jean-Jacques: Let’s say the lies are exposed, and America knows the truth – what will happen then? What will we do with that? What will we, sort of, gain from that?

Bailey: I think it might bring whites down off their high horses that they are some kind of great, spiritual people of the world and make them…stop presenting themselves as some kind of holy men of world history. I mean it’s going to be difficult. ‘Cause when you’ve been lying for 400 years, man, you– it’s gonna take a while. But it’s gotta be done. It is never gonna be that there’s gonna be some degree of real cohesiveness in this country. The truth has got to be told about how this country was built…

Jean-Jacques: Because…

Bailey: Because otherwise it’ll be constant conflict. You’re just not gonna get away with lying… This was wrong brother. It’s gonna be hard – it’s gonna be hard for them to admit the truth… ‘Cause they had been telling lies, man, and they’ve been consistently telling lies.

Bailey believes that Malcolm X would have spoken the same message – that America must not ignore its past which is littered with crimes against Black people. He mentioned the 300 years of free labor and that no other country in the world has had free labor for so long. Bailey then speaks on those who may not want the history to be revealed.

Bailey: ‘Cause many of us– and at a time I think it was a majority of us – we decided that for the goodies that we were getting in this country, we would just go along with just keeping quiet about the real history, and there are Black people today who don’t want the real history taught.

The conversation finished with Bailey’s thoughts on how Howard should contribute to the national discussion about racial equality. He emphasizes the importance of showing full, unprocessed history.

Bailey: Yes, they [HBCUs] should be places where you can go and learn the real history of the United States of America, and I’m not sayin all the things that we do– brother, believe me, there are some Black folks who I think are just skunks, but they’re part of our history so you gotta teach them. You cannot leave them out because you don’t like what they did. When you talk about Black history, you gotta talk about those people who were betrayers and who did things that hurt us. They got to be a part of teaching that history. You know, I’m not one of these people who say, ‘well just leave them out,’ no, ‘cause then we’ll be lying. We gotta teach the real histories of Black– and like any other group of people, some of it is positive, I think most of it is positive, there’s always some negative, and I say this to my African colleagues and friends, ‘the fact that Europoeans were able to do what they did to us was partially our fault.’ Because if we were a united people they would never have been able to do that.

Bailey was an associate editor at Ebony from 1968 to 1975. He has contributed articles to The Black Collegian, Black Enterprise, Black World, Essence, Jet, The Negro Digest, the New York Daily News, and The New York Times. He taught as an adjunct professor at Hunter College, the University of the District of Columbia, and Virginia Commonwealth University. Bailey has lectured at 35 colleges and universities around the country in the past few years. He also wrote a memoir called “Witnessing Brother Malcolm X: The Master Teacher” which was published in 2013 in paperback. He has written three other books called “Harlem: Precious Memories, Great Expectations,” “Revelations: The Autobiography of Alvin Ailey with Alvin Ailey” and “Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X with Rodnell P. Collins.” Bailey is currently working on a book called “Brother Malcolm X’s Strategic Pan-Africanism: An Important Guide For People of African descent.” He plans for this book to be released on May 19, the day of Malcolm X’s birthday.

Copy edited by: N’dia Webb