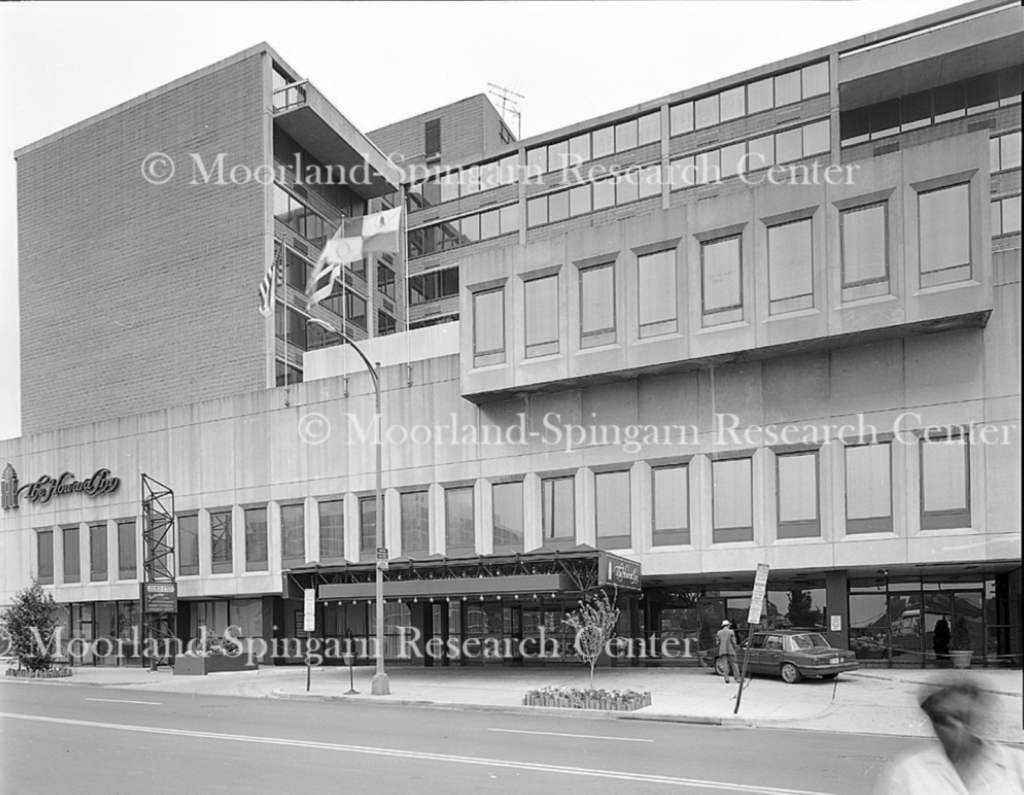

On the corner of Georgia Avenue and Bryant Street Northwest, the building that houses Starbucks, The Howard University Barnes & Noble Bookstore and the Axis residence hall was once a vibrant, sought-out hotel destination for Black people visiting Washington, D.C.

It began as the Harambee House when it was built and leased from the federal government by Ed Murphy, an African American entrepreneur, in 1979. According to the historical marker planted directly across the street, the hotel donned “African decor and high-end amenities” for notable guests such as Louis Farrakhan and Jesse Jackson. Stevie Wonder and Nancy Wilson played its infamous supper club, and Muhammed Ali, Coretta Scott King and Carl Stokes were just a few of the figures to host press conferences in the hotel’s Kilimanjaro Room.

Howard acquired the hotel from the Federal Economic Development Administration for $1.3 million two years later, and it became known as the Howard University Inn. However, the university never earned a profit from the hotel and closed it in 1995.

In an article from the Washington Post published that year, Murphy described his disappointment in the hotel’s closing.

“It was as if we were doomed from the start,” he said.

Around the corner from the former Howard-owned hotel is a sprawling brick complex known as the C.B. Powell Building. Before the pandemic, the building housed the School of Communications, but in 1862, it was a hospital for the formerly enslaved.

When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation the next year, freed slaves moving from the American South were considered “contraband.” They found refuge and medical treatment in what were called “contraband camps.” Camp Barker, near present-day Logan’s Circle, was one of them. Freedmen’s Hospital, where the C.B. Powell Building now stands, replaced the swampy plot of land Black people in the city went to for housing and healthcare.

In the late 1860s, Freedmen’s Hospital became a teaching school for Howard’s College of Medicine, where Powell graduated in 1920. He went on to practice medicine in New York City and later became publisher of one of the oldest Black-owned newspapers in the country, New York Amsterdam News.

When he died in 1977, Powell left about $6 million, the value of his estate, to the university. Two years later, the school named the building in his honor.

The C.B. Powell Building is mostly unused, though WHUR and WHUT, Howard’s two broadcasting units, still operate there. In 2022, the university announced plans to renovate the site to house a new STEM Center.

In 1929, word spread that a new building would be built on campus. Congress approved $1 million in funds—$17 million in today’s terms—to go towards the project. The plan was to demolish the Main Building and build a library in its place. It took seven years before construction broke ground and an additional three before Founders Library was complete and open to the public.

Rising to a peak of 167 feet, the Georgian-style building was one of several campus structures built by African American architect Albert Cassell.

According to the library’s website, Founders garnered national attention, was described as “a palace of books” and was the “most comprehensive library” of any HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) at the time.

Former U.S. Secretary of the Interior and advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harold Ickes, spoke at the library’s May 25, 1939 dedication ceremony.

“A library is more than a building, it is more than the volumes that rest upon its shelves…They constitute perhaps the most important single agency for the perpetuation of civilization,” he said.

The pathway from the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts to Founders Library used to be lined with trees. Today, most of the trees are gone, but the walkway that bisects the Yard is still known as “The Long Walk.”

When students graduate in May, it is tradition to walk “The Long Walk” in full regalia, symbolizing the completion of their Howard journey.

Copy edited by Jalyn Lovelady