The fashion world mourns the loss of legendary fashion writer, editor, stylist and North Carolina Central University (NCCU) alumnus, André Leon Talley, who was the first Black man to serve as the creative director of Vogue. He died of a heart attack at the age of 73 on Jan. 18.

While many may recognize Talley as the creative director of Vogue, or even the surveyor of “dreckitude” of cycles 14-17 of “America’s Next Top Model”, these are just a few of the hats that Talley has worn throughout his career. Talley had a talent for romanticizing the unassuming and adopting them into his world of grandiosity.

Friends and colleagues of Talley, including Noami Campbell, Marc Jacobs, Tom Ford and many more took to Instagram to remember him. Talley was described as “brilliant” and “larger than life,” with his heart a size that rivaled the grand energy of his presence. He saw some of these legendary figures from their burgeoning to their prime, all while becoming one of these figures himself.

Talley was born in the fall of 1948 in Washington, D.C.. Two months later, Talley moved to Durham, North Carolina, to live with his grandmother, a cleaning woman at the dorms of Duke University at the time. Before donning brocade kaftans and floor-length puffer coats, Talley would first find his affinity for style through the weekly bouts of fashion expression that came as Sundays in a Black church in the southern United States, which he attended religiously with his grandmother.

“Amidst the Jim Crow south, the Black Church was the only place, really, in which African-American life and African-American identity were affirmed and valued. And certainly, it was a fashion show. Members of African-American congregations put on their Sunday best. They changed from the uniforms, perhaps, or the work clothes that guided their lives Monday to Fridays, and on Sunday, that was the day that we would bring out absolute best to God,” Dr. Eboni Marshall Turman, a professor of ethics theology and African-American religion at Yale Divinity School and close friend of Talley, explained in The Gospel According to Andre, the 2018 documentary chronicling Talley’s life and legacy.

Talley often affirmed the impact that the upbringing with his grandmother had on his development into the figure that he would become. He loved her, admired her dedication for structure and cleanliness. He would note her collection of both gloves and handkerchiefs and her tendency to wear a dressy new hat for every occasion. She maintained this style, although according to Talley, many hat stores in Durham, North Carolina, had policies establishing that Black women were to wear veils when trying on hats, as not to allow their hair to touch the merchandise.

Talley discovered his first issue of Vogue in a public library and became enthralled in the world that the publication created.

“Every Sunday, after church, I’d have to go across town to the Duke East Campus, to the magazine stand to get the Vogues. And one Sunday I was going across the railroad tracks, and people threw rocks at me from a car. I wasn’t wearing capes or anything, I was walking around in a normal… ski sweater or something. And I thought that–this was a bunch of white boys at Duke–decided to throw rocks at me because I was walking the campus. But I was taught to rise above it and to be strong,” Talley retold in his documentary.

This was the reality for Talley. The energy of glitz and glamour that he would exude, the ease with which he appeared to navigate the world, a 6’ 6 Black gay man. The picture of decorum, grace and sass would make him a constant subject of anger and racism. His position was not without struggle. Nevertheless, he persevered.

His passion for the French language and culture, which he credits in part to his fascination with Julia Child, led him to study French Literature at NCCU, a historically Black college and university (HBCU) in his hometown. His attendance at the school would inspire NCCU students long after his matriculation.

“André Léon Talley was the reason I decided to go to NCCU instead of my dream school. The first time I was introduced to André Leon Talley was on America’s Next Top Model. Seeing a Black man be so powerful in the industry was inspiring,” Sydni Mottley, a senior Family Consumer science major with a concentration in Apparel Design and Textile at NCCU, said.

“After watching the September Issue, I only gained more respect for him. Seeing him be so successful made my dream of being in the fashion industry possible. I also appreciated that no matter how successful he got, he always supported his community. Whether that be going back to his high school in Durham, North Carolina, or working with the Obama’s during their time in office by dressing Michelle in designs by Black and minority designers,” Mottley continued.

After graduating from NCCU, Talley pursued his master’s degree in the same subject at Brown University in Rhode Island, where he truly began to entertain his passion for style. He frequented Rhode Island School of Design, where he and his friends would dress up nearly every weekend to go nowhere in particular.

“Brown gave me a freedom, a liberation that propelled me into the world that I know,” Talley documented.

Talley graduated from Brown University with resolve. In 1974, he moved to New York, where he would secure his apprenticeship under Diana Vreeland at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vreeland would later become the editor-in-chief of Vogue. He often likened her focus and meticulousness to that of his grandmother, so much so that he would later dedicate a room in his late grandmother’s house to Vreeland. She was Talley’s formal introduction into the world of fashion, and from there, his career propelled.

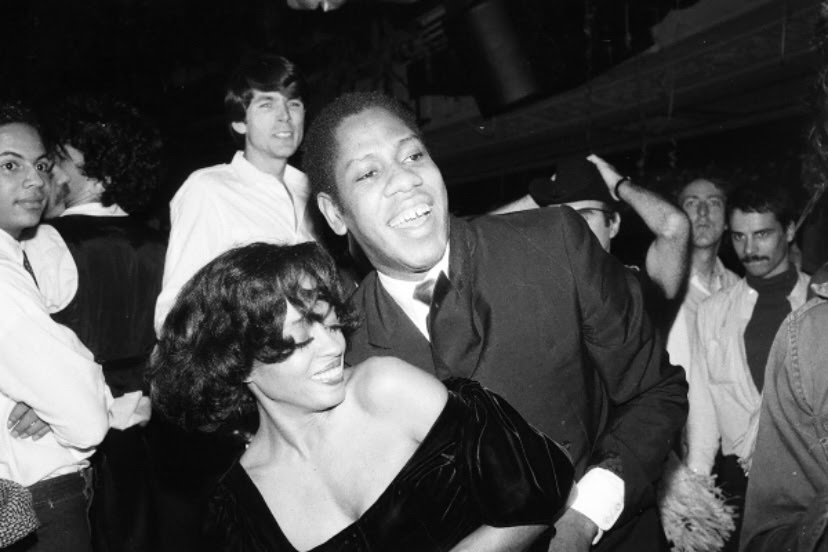

His experience with Vreeland would lead Talley to work as a receptionist for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, where he would develop a close friendship with Warhol. It was during this time that he would meet another mentor and friend: Karl Lagerfeld.

“Karl mentored me in everything: French history, literature, the history of fashion, art. From our first moments, we were like the brother each of us wished we had, true siblings. Even on that first May afternoon, he invited me to his bedroom suite, simply to throw the most luxurious silk shirts from his Goyard trunks at me. I walked away with a wardrobe of beautiful shirts, his own, and matching mufflers,” Talley wrote in a Vogue article following Lagerfeld’s passing in 2019.

Later he would move to become the Paris Bureau Chief of Women’s Wear Daily, in France, where his mastery of the culture and language would give him the upper hand.

When Talley first began his career at Vogue as the fashion news director in 1983, it was under the leadership of then editor-in-chief Grace Mirabella. In both his memoir and his documentary, Talley recalls less than favorable encounters with the editor. In one instance, according to Talley, to demonstrate the origins of Yves Saint Laurent’s use of feathers, Talley suggested to Mirabella that they include a photo of an African man with feathers in his hair in an issue. To this, Mirabella was taken aback, and asked Talley, “What have I done to deserve this underground influence?”

Experiences like this would inform much of the work that Talley would do as a creative director under Condé Nast. He refused to shy away from starting “uncomfortable” conversations and putting Black people at the forefront of fashion.

In 1996, he styled his famous Vanity Fair spread “Scarlett ‘n the Hood,” a fashion infused spoof on “Gone with the Wind,” in which he reversed the roles of servitude and aristocracy as they pertain to race. In this spread, John Galliano was a servant, Manolo Blahnik a gardener, and Naomi Campbell his Scarlett O’Hara in Givenchy, Dior, and Chanel.

Talley wasn’t just a creative, he was a Black creative, which he aimed to make abundantly clear throughout his career.

“Race does define me,” he told Robin Givhan of The Washington Post in 2018. “It feels more relevant now to bring it to the forefront.”

He had to traverse the “Chiffon Trenches,” as he would call them–which would be the namesake of his 2020 memoir–not only to topple the barriers in place that prevented Black people from prospering in the world of style, but to create his own world. A world in which Black models are depicted in the lap of luxury. A world in which Black designers from which so much of fashion is stolen finally get a seat at the table. Fashion history will remember André Leon Talley as a superhero in a fur cape.

“Create your own universe and share it with people that you respect and love”

-André Leon Talley in The Gospel According to Andre

Copy edited by Jasper Smith