By Amerra Sheckles, News Staff Writer

Posted 12:17 PM EST, Fri., Sept. 23, 2016

Fall semester hit Howard University, classes have officially begun and campus feels lively once again. However, aside from the returning students and the unchanging, everlasting “Howard struggle,” not much feels or even looks the same.

All of the old faces that used to walk the campus have graduated and started new lives, while many of us have returned this semester to continue our pursuits and education.

As the year begins, the freshman begin learning more and more about the cultures and traditions of Howard. Expectations may be confirmed, but some may not. For instance, the uncertainty of Howard Homecoming and the changes current Howard students have seen in the past two years.

Beginning after the last “real” Homecoming, there has been a distinct disparity between “Old Howard” and “New Howard.” Overwhelmed by the growing dissension of Howard’s returning students, it became clear to me that change, and not necessarily change for the better, hit campus hard.

Howard classics such as Yardfest still technically exist (as the 2016 Howard Homecoming Steering Committee recently announced that “Yardfest is officially back”), but the relationship between the old traditions and current Howard students feel like it has been severed.

…yes, for free #ExperienceBlueprint pic.twitter.com/bUbT79RIij

— Howard University Homecoming (@BisonHomecoming) September 20, 2016

“Yardfest is back.” We can’t say it any clearer.

Howard, old and new, you’re welcome! Sincerely, BLUEPRINT#ExperienceBlueprint

— Howard University Homecoming (@BisonHomecoming) September 20, 2016

“We as students and alumni make Howard; we are Howard.” said 2016 graduate Darieal Wimbley. “It is our long nights, tears, love and sacrifices that keeps and kept Howard afloat, and the same goes for its tradition and future.”

Now that I have spent some time as a Howard student and I have learned through both experience and the opinions of HU students and faculty, I can see for myself that with each new year, “New Howard” keeps getting “newer.”

With a new president, new dorms and new institutional policies in place, Howard now resembles more of battlefield between the superimposition of a more modern appearance. Regardless of the impacts on the culture already in place and the loosening grip, its students sustain the beauty of Howard’s rich history and traditions of academic excellence and service.

The more D.C. visibly changes, the more modified the appearance of Howard’s campus seems to become in order to better match the aesthetic of gentrified D.C. Modifications which have been most recently exemplified by the additions of more modern looking buildings, like College Hall North and South, as well as Howard’s brand new Interdisciplinary Research Building on Georgia Avenue.

The Washington Post states that today, in neighborhoods such as Georgetown, where the African-American population was at 40 percent in the 1800s, is at the rate now at about three percent.

With each new year, there are more and more noticeable changes that are also around Shaw-Howard. Washington, D.C. has begun to shift from “Chocolate City” to “Latte City,” as Petula Dvorak, columnist for The Washington Post proclaims, and Howard University is no exception.

The more gentrified the city becomes, the more the University seems to contribute to it and consequently, the further Howard moves from this concept of “Old Howard” toward the new.

“It’s so white, folks have a hard time figuring out what Black people are doing when they go there,” Dvorak said in the article.

According to Mike Miciag for Governing Magazine, Washington, D.C. is “home to some of the country’s fastest-gentrifying communities.” This includes communities like Columbia Heights which is next door to Howard University.

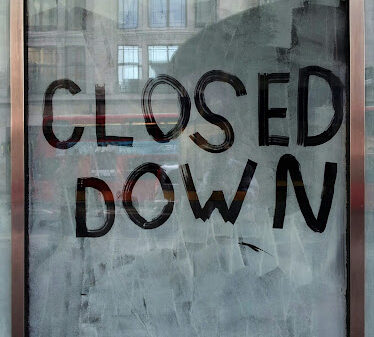

Since fall 2014, U Street has transformed into a posh neighborhood full of quirky restaurants and luxury apartments far outside of the budget for the majority of college students. Georgia Avenue now plays host to the juxtaposition of an impeding gentrified culture caused by the influx of middle class, white D.C. residents and the pre-existing black owned businesses and entrepreneurs that exemplify D.C. Africana culture.

“It’s like they’re squeezing a pimple. Gentrification is pushing in on Howard from every direction and that just somehow makes me feel unsafe,” said Jahlik Parkes, a junior architecture major.

In the past six months, Howard staples like Howard China, or “HoChi,” has adapted to the shifting Shaw-Howard community by improving its outer appearance to match the new, shiny glitz and glamour creeping up and over from 14th and U streets.

The increasing changes are not always negative, but they are driving out the old in order to make room for the new that creates the negative impacts Howard has been exposed to.

“The way gentrification works, they’re going to start raising the price of the little things. The cost of living on campus will go up and they might even raise the price of tuition. Then it will become more expensive to eat around campus until eventually, you end up hungry with no classes, wondering what’s going on,” Parkes explained.

Even though many Howard staples are still in place, the new culture of Shaw-Howard has impacted the way students are allowed to interact with their traditions.

The chipping away of Howard property and historical Shaw-Howard establishments obstructs the connection between “Old Howard” and “New Howard,” preventing new students from establishing new relationships with old, historic Howard monuments and traditions.

“Howard has a lot of tradition, traditions that should be honored; but, as society and student culture continue to change and develop, some Howard traditions may not make the cut,” Wimbley said. “As a community we can change the realities of gentrification and it starts with the student and alumni relationship and creating common ground.”

Howard students should be encouraged to find some way to raise money without selling off our assets since the selling off Howard assets only contributes to the issue of gentrification in D.C.

“We can invest in the school so that things can become more organized. We need to improve the school internally,” said Zane Cribbs, a Class of 2016 Howard graduate.

This is not to say progress and change are not to be encouraged. Instead, the imposition of change should be evaluated to ensure the consequences do not outweigh the benefits.

Ultimately, the blight of gentrification is present and will continue to persist in the communities surrounding Howard University. Washington, D.C. will continue to develop and to change until it carries little to no resemblance to the city it once was.

We, as contributors to Howard culture, should be critical and question whether these changes are possible without compromising the traditions and integrity of the school because as students. We have the power and the privilege to engage in, preserve and pass along the traditions that were once passed down to us.

There would be no institution were it not for the students, so as long as we uphold and preserve our traditions, the integrity of the school and its culture cannot be compromised.