By Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer

Posted 11:00 AM EST, Fri., Sept. 2, 2016

From Biggie Smalls to Spike Lee, Brooklyn, New York has been known as a hotbed of Black creativity. In 2005, when Los Angeles filmmakers James Spooner and Matthew Morgan set out to created a festival based on their documentary, AfroPunk, Brooklyn presented itself as the perfect womb to carry their idea.

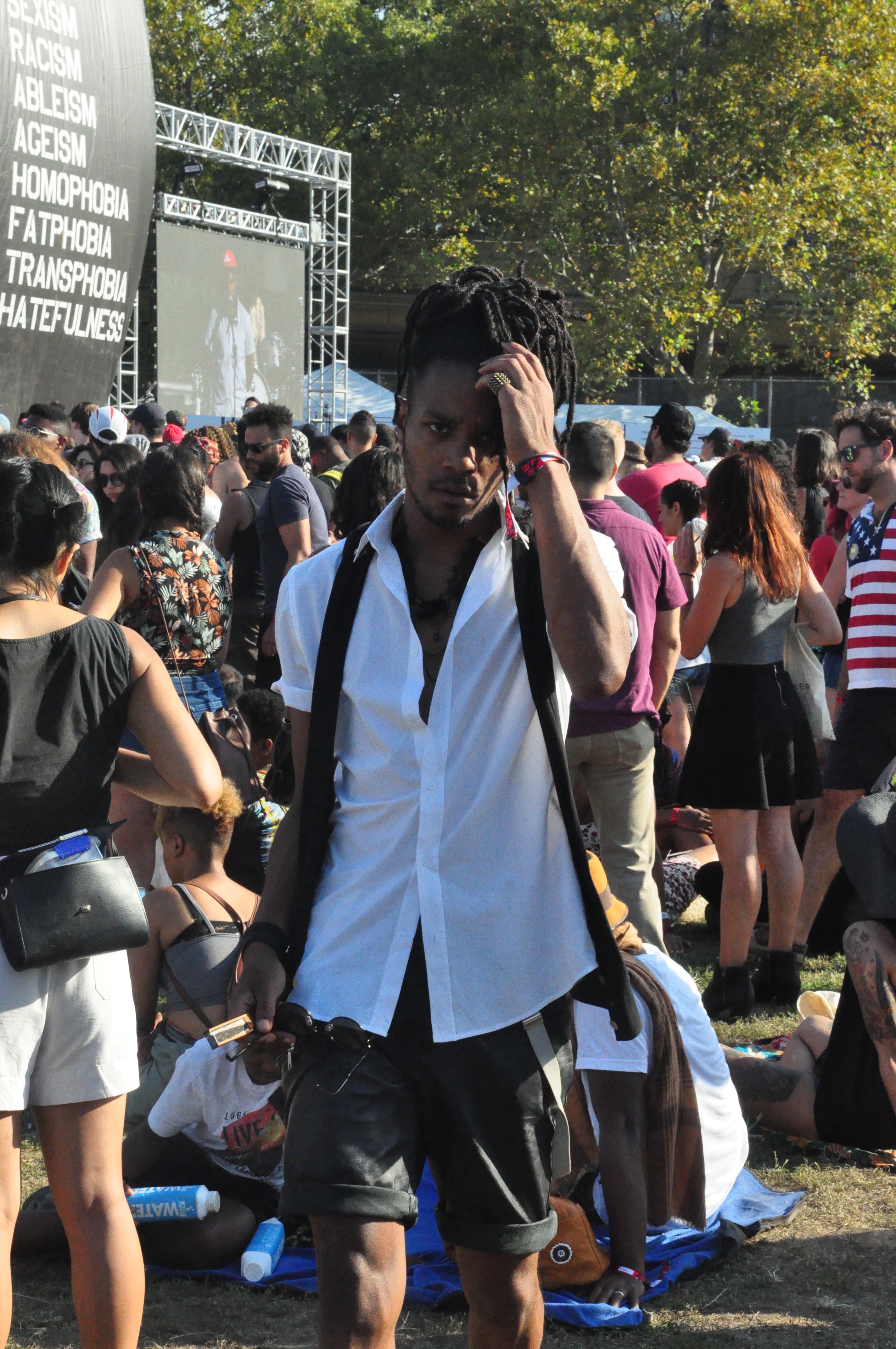

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

- (Photo Credit: Jaylin Paschal, Culture Staff Writer/The Hilltop)

Since then, the massive popularity of AfroPunk has extended past its Brooklyn roots to a Paris, London and Atlanta event annually. Uniquely, the vibe of AfroPunk offers the opportunity for uncensored black dialogue on racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and other marginalized issues. The festival brands itself as ‘the other black experience:’ a blend of aesthetically black musical performances with articles, artwork, music, artist information and videos compiled online for easy access and sharing. And ‘other’ experience it certainly is; it seemed tolerance and acceptance were the only true rules of this summer’s AfroPunk celebration at the Commodore Barry Park in Brooklyn on August 27 and 28.

The music lineup on that weekend brought out thousands of fans from across the nation, representing every demographic imaginable. Four stages filled the green of the Brooklyn park, with headliner Ice Cube, CeeLo Green, The Internet, Tyler, the Creator, Janelle Monae, George Clinton, and many other artists. From noon to midnight each day of the festival, colorful afros and flower crowned locs bobbed to alternative and hip hop music.

Vendors outlined Commodore park, selling everything from natural hair care products and dashikis, to Malcolm X apparel and handmade jewelry. Food vendors served a tantalizing range of Pan-African and diasporic dishes.

Of the multitude of attractions offered at AfroPunk however, Activism Row was perhaps the most unique.

This year’s Activism Row booth display featured movements like Black Lives Matter and hosted local organizations to register young voters and stop the gentrification of Brooklyn neighborhoods. Legendary poet Dr. Nikki Giovanni visited the booths that day, tearfully expressing her pride in young black activists’ modern fight for racial equality.

At AfroPunk, a “Black” standard of shape, size, hair or music could not be found. There was no “acting Black.” For two days, it was as though there was only blackness in a pure and unapologetic form, as collective experiences melded together to create an amalgam of ‘other’. If ever a space could alleviate the suffocation of constant oppression, it was AfroPunk: one could definitely breathe there.